Understanding Indications and Implications of End-of-Life Care in the ICU

The Indian Perspective 🇮🇳

End-of-life care (EOLC) is a profound and challenging aspect of modern medicine, demanding a delicate balance between ethical, clinical, emotional, and financial considerations. This narrative explores the complex landscape of EOLC in India, weaving together the role of technology, cultural influences, and systemic challenges with the indications, implications, and evolving frameworks guiding practice.

Opening Reflection: A Letter 📨to My Doctors 🥼

Constantinos Kanaris’s poignant words encapsulate the moral dilemmas faced in critical care:

“I was born premature, 4 months early. You intubated me, put me on a ventilator, because You could… It went on for days. My parents said STOP. The last straw. They finally could… If You had known what my future held, Would you listen to me on day one? Would You stop?”

This letter underscores the ethical complexities surrounding life-sustaining treatments, particularly in situations where outcomes are uncertain or inappropriate. It is a clarion call 📢 for healthcare professionals to balance technological possibilities with the art of compassionate care ❤️🩹.

The Modern Dilemma: Technology vs. Humanity

Technological advances in critical care have undeniably transformed outcomes for many, yet they also pose challenges:

1. Loss of the Human Touch 🩻➡️🤝: As medicine becomes increasingly evidence-based, the focus on metrics 📊 and interventions risks overshadowing the personal and emotional needs of patients and families 🧑🤝🧑.

2. Aging Population and Chronic Illness 📈👵: With rising life expectancy and an increasing burden of chronic illnesses, ICUs are often at the intersection of curative and palliative goals 🏥.

3. Decision Paralysis 😕: The ability to sustain life indefinitely using technology sometimes leads to prolonged suffering 😞, creating dilemmas for clinicians and families.

These challenges are particularly pronounced in India, where cultural norms, resource constraints, and evolving legal frameworks add layers of complexity to EOLC decisions.

Indications for End-of-Life Care in the ICU

EOLC is appropriate in situations where curative treatments are no longer beneficial 🚫🩺, and the focus shifts to comfort care 🤲💗. Common indications include:

1. Irreversible Multiorgan Failure 🫀🫁: Despite maximal intervention, survival is unlikely.

2. Terminal Illnesses 🛑🎗️: Advanced malignancies or neurodegenerative conditions with no curative options.

3. Persistent Vegetative State or Brain Death 🧠❌: Confirmed by established diagnostic criteria.

4. Refractory Conditions 🌪️: Such as severe ARDS or septic shock with a poor prognosis.

5. Patient-Centered Requests 🤝: Advance directives or decisions made by surrogate decision-makers.

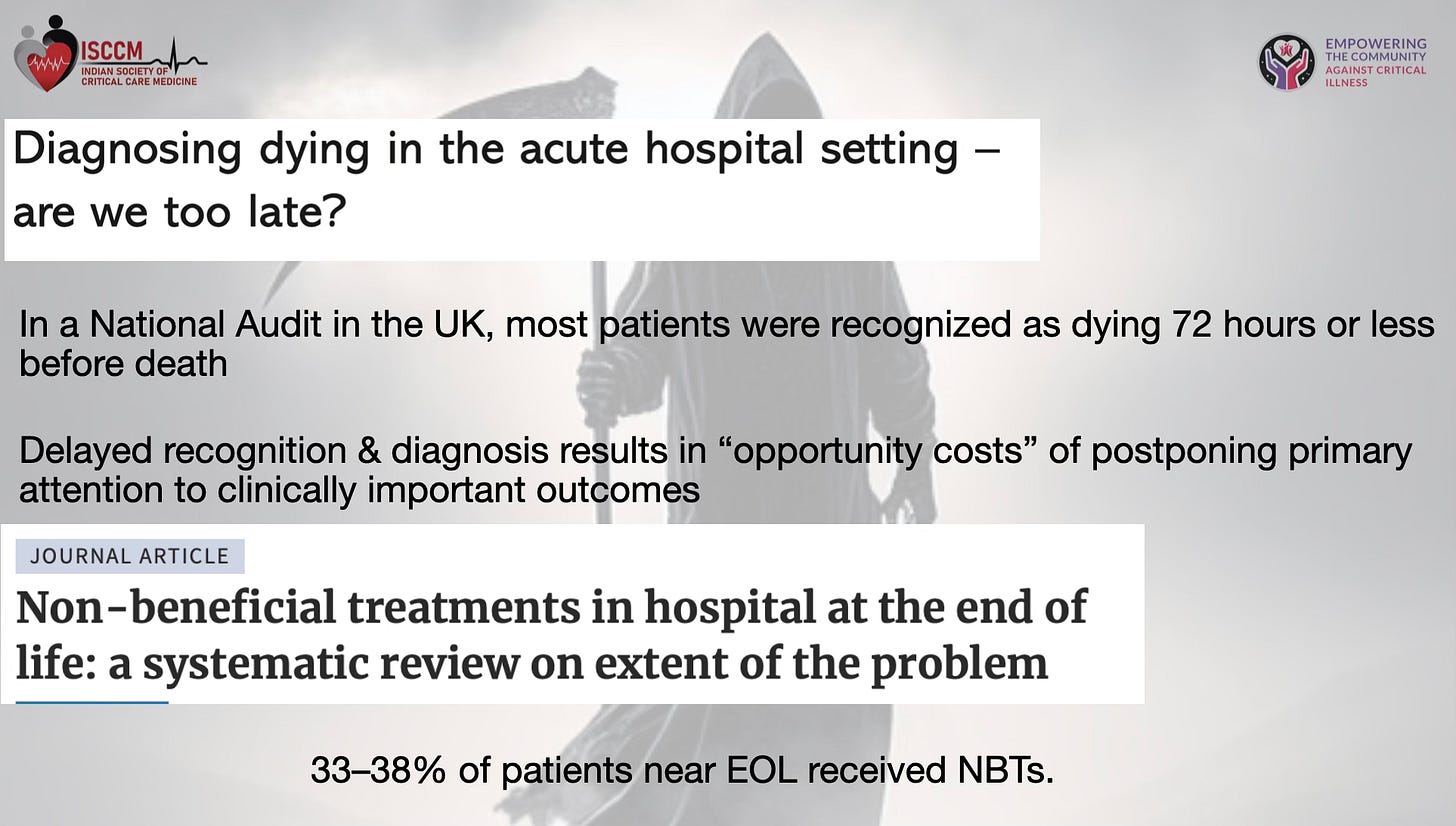

Even though these indications are clear, we still do very poorly at transitioning from curative care to end-of-life care. In a national UK audit “Diagnosing dying in acute hospital setting—are we too late?”, most patients were recognized as dying 72 hours or less before death. Delayed recognition and diagnosis result in the “opportunity cost” of postponing primary attention to clinically important outcomes.

If we look at the systematic review “Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at end of life: systematic review on extent of problem”, 33–38% of patients near EOL received non-beneficial treatments. Why do we perform so poorly? Upon introspection and reviewing the evidence, it is clear that physician 👩⚕️ 🧑⚕️ prognostic abilities are often hampered by personal bias, communication skills, over-optimism, unwillingness to face moral dilemmas, self-fulfilling prophecies, and an inability to handle uncertainty and risk in early prognostication. In the Indian context, this problem is exacerbated by:

• Lack of universal awareness about advance directives,

• Cultural emphasis on “life at all costs,”

• Limited availability of palliative care resources,

• Variability in hospital EOL policies,

• Family-oriented decision-making rather than individual-oriented.

To bridge this gap, ISCCM and IAPC have jointly ventured to bring forth the position statement in 2024, focusing on the principles of a human-centered approach. They beautifully elucidated the trigger points to consider initiating EOLC discussions with families.

These trigger points include:

1. Catastrophic brain injury (e.g., traumatic brain injury, massive acute ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, brain infections, demyelinating diseases, septic encephalopathy) with coma (other than brain death) and poor prospects for meaningful neurological recovery.

2. Critical illness on a background of irreversible severe neurological disability, such as traumatic quadriplegia or end-stage muscular dystrophies.

3. Critical illness on a background of chronic irreversible disorders of consciousness, such as advanced dementia, minimally conscious state, or permanent vegetative state.

4. Post-cardiac arrest anoxic-ischemic injury with Glasgow Motor Score ≤2 and neurophysiological markers of poor prognosis >3 days after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), having excluded confounding factors.

5. Advanced or metastatic malignancy with short median survival rates if treatment options are exhausted or declined by the patient.

6. Advanced age with declining functional status and frailty or multiple comorbidities where interventions have a low probability of success or are declined by the patient.

7. Acute decompensation of chronic end-stage organ failure such as pulmonary, cardiac, renal, or hepatic with low life expectancy and no option of organ transplantation; ≥3 hospitalizations in the last 12 months.

8. Worsening multiorgan failure (e.g., SOFA >15) due to acute conditions refractory to a reasonable trial of organ support.

9. Any patient who expresses a desire against aggressive care or a patient without decision-making capacity with previously executed valid Advance Medical Directives (AMD) declining such care.

10. Any other clinical scenario where the answer to the question “Would you be surprised if the patient is alive at the end of 6 months–1 year?” is “Yes.”

However, EOLC decisions are much more complex. To decide on the EOLC pathway, the physician must be reflective on their prognostic abilities to determine the inappropriateness of life-sustaining therapies through early discussions with the patient and family. Once decided on EOLC, the implications are multidimensional.

Implications of EOLC: A Multidimensional Perspective

Positive Implications ✅

• Dignified Death 🕊️: Facilitates a peaceful transition, respecting the patient’s wishes.

• Empowered Families 🙌: Reduces uncertainty and guilt through informed decision-making.

• Resource Optimization 📉💡: Avoids non-beneficial interventions, ensuring better allocation of ICU resources.

• Ethical Alignment ⚖️: Reflects principles of autonomy, beneficence, and non-maleficence.

Negative Implications ❌

1. Family-Related 👨👩👧👦

• Emotional Distress 😢: Families often grapple with guilt, grief, and confusion.

• Conflict ⚔️: Diverging opinions among family members can delay decisions.

• Cultural Pressures 🛐: Religious beliefs and societal expectations may compel families to “do everything possible,” even when outcomes are non-beneficial.

2. Clinician-Related 👩⚕️👨⚕️

• Burnout and Moral Distress 🔥💔: Prolonged exposure to EOLC scenarios takes an emotional toll on healthcare providers.

• Communication Gaps 🗣️🔇: Many clinicians are ill-prepared for difficult conversations about death.

• Fear of Litigation ⚖️🛑: Concerns about legal repercussions discourage proactive EOLC discussions.

3. Legal ⚖️

• Ambiguity 🤷: Despite the 2023 Supreme Court judgment on Advance Medical Directives (AMD), implementation remains inconsistent.

• Litigation Risk 📝⚠️: Inadequate documentation or miscommunication can lead to legal challenges.

4. Ethical 🤔

• Conflicting Principles ⚖️❓: Balancing patient autonomy with family preferences often leads to ethical dilemmas.

• Resource Allocation 📊: Prolonging non-beneficial care may unjustly consume resources needed by others.

5. Sociocultural 🌏

• Cultural Taboos 🙊: Discussions about death are often avoided in Indian society.

• Religious Influences 🙏: Beliefs in divine intervention can delay or complicate EOLC decisions.

6. Organizational 🏥

• Resource Strain 🏋️: Prolonged non-beneficial care consumes ICU beds and staff time.

• Policy Gaps 📖: Many institutions lack clear protocols for EOLC.

• Palliative Care Integration 🌱: The absence of palliative care teams results in fragmented care.

7. Financial Implications 💰

• High Healthcare Costs 💸: Extended use of life-sustaining technologies can significantly increase costs, especially when the outcome is non-beneficial.

• Family Burden 💳: ICU care expenses often lead to financial strain for families, especially in the absence of insurance coverage for palliative care.

• Resource Misallocation 💵: Non-beneficial treatments divert funds from other critical healthcare needs, leading to inefficiencies.

• Lack of Insurance Support 🏥: Many insurance plans do not cover palliative or hospice care, adding to the financial burden for families seeking quality end-of-life care.

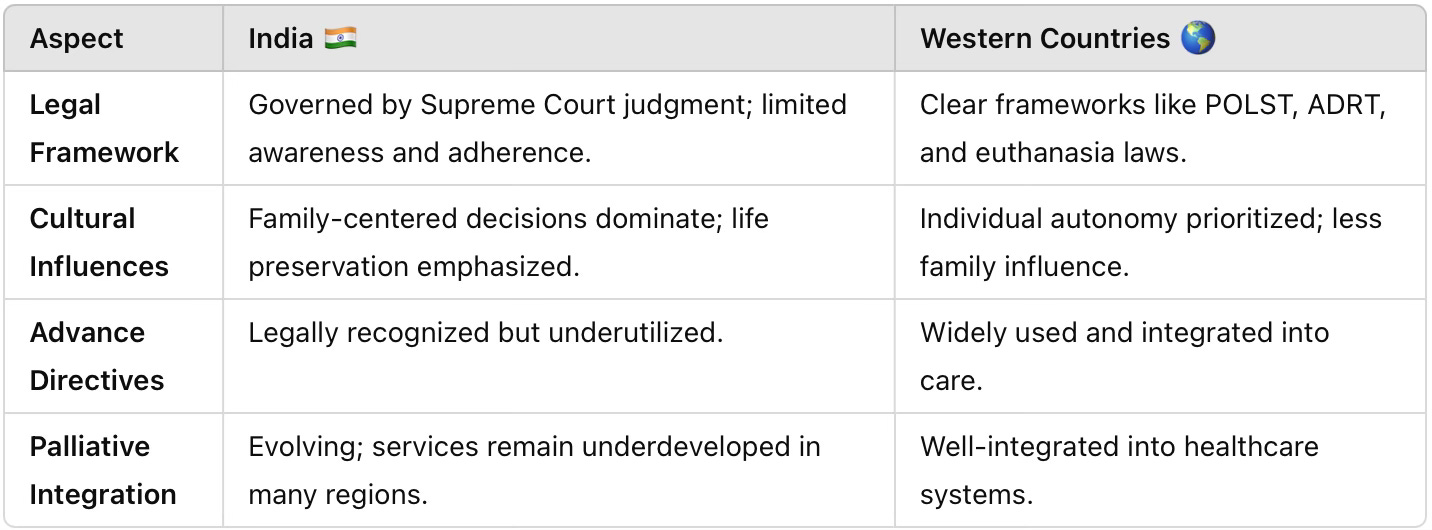

EOLC in India vs. Western Practices 🌍

A comparative analysis highlights stark differences:

Framework for EOLC: Recent Guidelines 📜

1. 2023 Supreme Court Judgment on AMDs ⚖️

• Recognizes legally binding AMDs with clear procedural guidelines.

• Advocates for medical board oversight in withdrawal decisions.

2. 2024 ISCCM-IAPC Position Statement 🏥

• Defines EOLC pathways: withholding, withdrawal, and comfort care only.

• Encourages early integration of palliative care.

Addressing Challenges 🚧

To improve EOLC in India, the following steps are essential:

• Education 📚: Structured training in communication and palliative care.

• Awareness 📢: Promoting AMDs and EOLC principles among families and clinicians.

• Systemic Changes 🏗️: Enhancing resources and developing institutional protocols.

• Legal Safeguards 🛡️: Addressing gaps in implementation to reduce fears of litigation.

Conclusion 🤝

End-of-life care in India is an evolving domain, shaped by unique cultural, legal, financial, and systemic factors. By prioritizing compassionate care ❤️🩹, fostering open communication 🗣️, and adhering to ethical principles ⚖️, intensivists can ensure that EOLC respects the dignity of every patient while addressing the needs of families and the healthcare system.

This journey requires not just adherence to guidelines but a commitment to preserving the humanity at the heart of medicine. As Kanaris’s letter reminds us, the true art of healing lies in knowing not just what we can do, but what we should do. 🕊️

References:

1. Kanaris C. A letter to my doctors. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(4):379-380. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001920.

2. Hasegawa K, Shiraishi A, Takahashi H, et al. Diagnosing dying in acute hospital settings: are we too late? A UK national audit. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(9):1477-1485. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4417-7.

3. Bacigalupo A, Varnier M, Bensouna I, et al. Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at end of life: systematic review on extent of the problem. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11(3):317-324. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002537.

4. Sharma R, Bajwa SJS, Mohta M. Critical care ethics: end-of-life care, palliative care, and organ donation in the ICU. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(9):689-694. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23389.

5. Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine (ISCCM) and Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC). Position statement on end-of-life care and palliative care. 2024. Available from: https://www.isccm.org/

6. Supreme Court of India. Judgment on Advance Medical Directives (Living Will). 2018. Available from: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/189406097/

7. Jha S, Mehta S, Nair N, et al. Palliative care integration in critical care units in India: status and challenges. Indian J Palliat Care. 2022;28(4):483-490. doi:10.4103/ijpc.ijpc_128_22.

8. Gopalan S, Ravikumar A, Vinod K, et al. Understanding the implications of end-of-life care in India. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(1):29-35. doi:10.4103/ija.IJA_92_18.

9. Royal College of Physicians. End-of-life care in the ICU: Guidance for practitioners. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2020. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/end-life-care

10. World Health Organization. Palliative Care: The Solid Facts. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/palliative-care-the-solid-facts